Changing Perception Through Lived XXY Experiences

Discover real-life stories, tools, and hope from the XXY community. We’re reshaping the narrative around Klinefelter syndrome through empathy, connection, and lived truths.

About XXYShare Stories

We share real experiences from individuals with XXY.

Build Awareness

We educate parents and professionals with engaging content.

Create Change

We partner with the community to challenge stigma and drive advocacy.

Sharing Real Stories To Inspire Others

We are a nonprofit platform providing real experiences, support, and education to help the XXY community and their supporters thrive.

- Amplifying voices across the XXY spectrum

- Offering multimedia educational tools and resources

- Connecting families, adults, and healthcare professionals

We aim to change how the world views Klinefelter syndrome by focusing on real experiences, spreading positivity, and empowering the XXY community through awareness, support, and education.

Learn More About UsExplore Our Resources And Support Tools

Youtube

Using video to help educate people on how to best advocate for themselves, on such topics as, improving social skills, testosterone and dealing with depression & anxiety.

Podcast

Through personal connections from different generations, we can ensure that people learn how to overcome challenges they may face by listening to others experiences.

Testosterone Replacement Therapy

Learn about testosterone replacement therapy options, benefits, and considerations for managing Klinefelter syndrome, helping you make informed decisions about your treatment journey.

Infertility

Having Klinefelter syndrome does not mean your hopes of fatherhood or parenting are impossible to achieve, as many individuals find ways to create loving families.

Early Intervention Services

Through personal connections from different generations, we can ensure that people learn how to overcome challenges they may face by listening to others experiences.

Research Index

Here is a collection of research papers written on Klinefelter Syndrome. We have put all papers we could find in one place for you to access easily.

Dispelling Myths About Klinefelter Syndrome

From lack of diagnosis to misleading information, we work to overcome the common challenges faced by those living with XXY.

- Between 1-400 to 1-650 Males are born with Klinefelter syndrome. Only 35% will be diagnosed at some point in their lifetime, 65% will never know.

- Google Search – Information is very negative and only talks about health related issues and educational problems. Lacking positive information.

- Old Images – Photos are way past their prime and depict a very small part of the spectrum.

- Spectrum – Little understanding on the degrees of variance.

- Lack of Research – Insufficient number of clinical trials and knowledge on what to study.

Start Strong With Early Guidance

Early education and support can transform outcomes for XXY children. Our tools and advice help families from the start.

- Speech and cognitive development resources

- Community stories to guide your journey

- Tools built for the XXY learning style

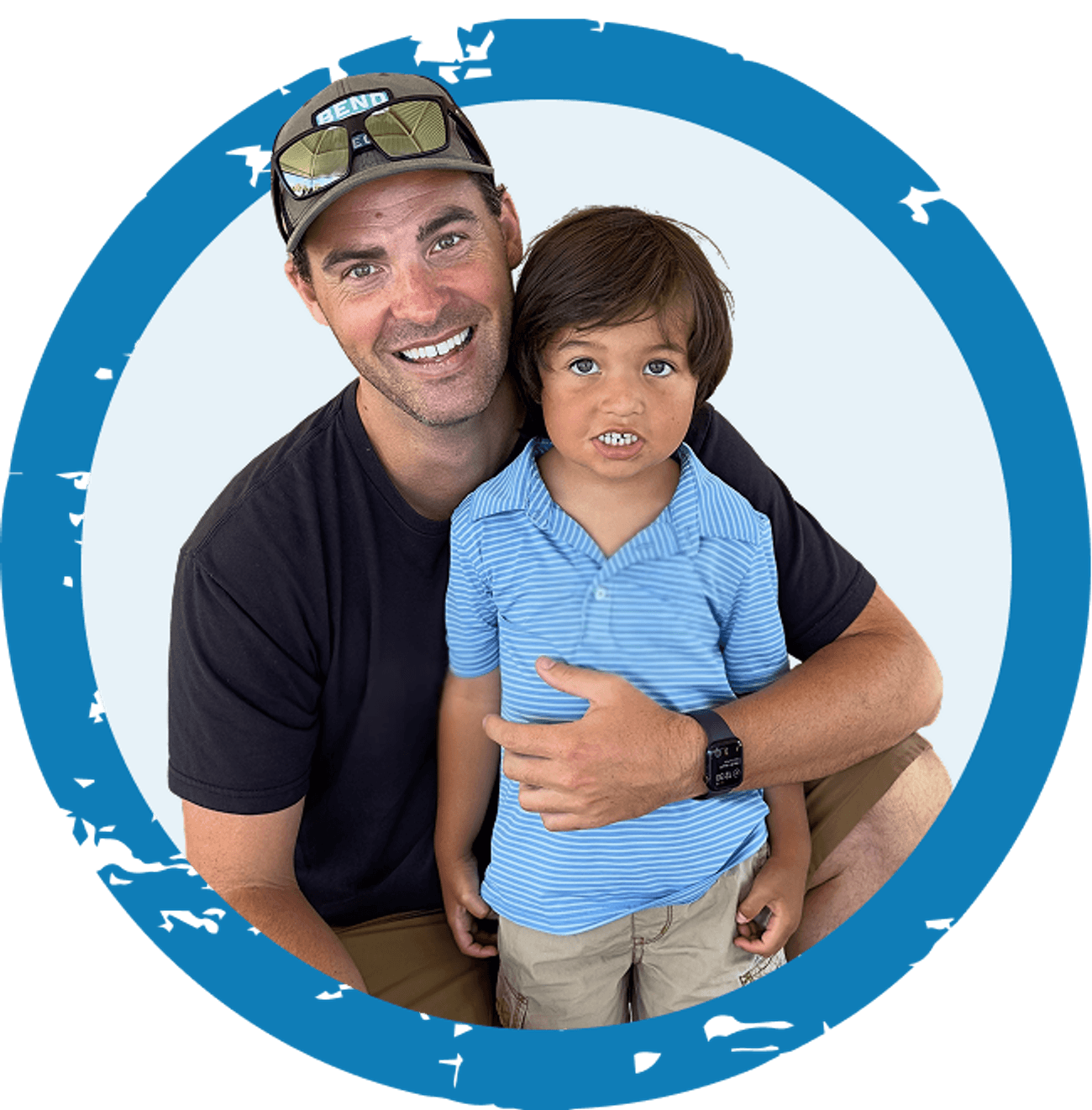

Fatherhood Is Still An Option

Infertility is a challenge—not an end. We share pathways and support systems for family-building with XXY.

- Learn about IVF, IUI, and donor sperm

- Discover surgical options like micro-TESE

- Hear empowering stories from XXY fathers

Dedicated To Changing XXY Lives Together

Ryan Bregante Founder

Ryan Bregante Founder Shanlee Davis Medical Advisor

Shanlee Davis Medical Advisor Tyler Indermill Advocate

Tyler Indermill Advocate Gareth Landy Advocate

Gareth Landy Advocate

Real XXY Stories, Real People, Real Impact

Dive into our engaging video series featuring inspiring stories of education, self-advocacy, and motivation shared by authentic voices from the vibrant XXY community, showcasing their unique journeys.

What Our Community Says

- A Anonymous

Our little XXY boy officially here! I cannot thank you enough for this platform and resources! We are so prepared to give this little boy everything he needs. We have learned so much from you and your guests & support. Thank you!

- L Lisa T.

As a parent, I was overwhelmed after my son’s diagnosis. This community gave me hope, knowledge, and a sense of peace we never had before.

- A Anonymous

I just got the call today. I am 11 weeks pregnant, and my doctor told me that we will talk about termination at my appointment with the geneticist. Holy crap, that was hard to hear. I am incredibly grateful to have found this video because Google is a nightmare.

Insights from the XXY Community Blog

- May 4, 2025

I Felt Like Something Was Missing.

At 21, Cesar’s Air Force dreams uncovered a surprise diagnosis: Klinefelter Syndrome. He turned adversity into confidence being XXY.

Read More - Apr 25, 2025

Tyler Indermill - I have forty-seven chromosomes! - Living with XXY Non-Profit

When Tyler Indermill was diagnosed with Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) at age 33, it changed his life—but not in the way he expected.

Read More - Apr 12, 2025

Finding Your XXY Parenting Community

With time I’ve developed a community of Klinefelter syndrome moms. There’s such importance in finding your XXY parenting community.

Read More

Common Questions About Living With XXY

Explore More- 65%

Undiagnosed conditions lead to a lifelong lack of awareness and understanding.

- 85+

Research papers since 1942 which have advanced the field significantly.

Klinefelter syndrome is a genetic condition in boys and men who have an extra X chromosome.

Klinefelter syndrome is caused by having many extra genes on the additional X chromosome. We do not know exactly how these genes lead to the features of the condition.

Klinefelter’s, 47,XXY, XXY, XXY syndrome, and KS are all different names for Klinefelter syndrome.

Studies show 1 in 500-1000 males have an extra X chromosome.

Historically, studies have shown that ~2/3 of boys with KS were never appropriately diagnosed. These numbers may be decreasing as genetic testing, especially prenatal genetic testing, becomes more common.

Stay Informed With Every Update

Sign up to receive our latest stories, educational resources, and opportunities to connect with others in the XXY community.

Join The Community Today