Written By: Chelsea Castonguay

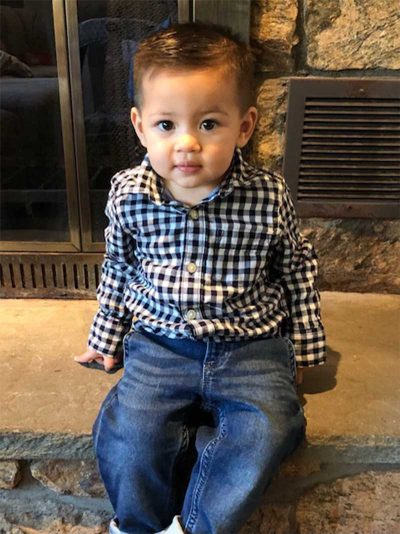

Melissa and her family live in New York state. She and her husband Ryan share a five-year-old daughter, Ava, and Jack, their son with XXY. Jack will turn two in May 2021. Melissa recently shared the story of what it was like to receive a prenatal diagnosis of 47 XXY, the process of getting him the right support services, and how Jack is doing today.

Diagnosis:

After a smooth pregnancy and birth with their daughter Ava, Melissa, and her husband looked forward to expanding their family. In between Ava and Jack, Melissa experienced a miscarriage. She and her husband began trying to conceive again through In Vitro Fertilization, more commonly known as IVF. While in the midst of an IVF cycle, Melissa spontaneously became pregnant. The couple was excited to welcome a new member into their family, and looking forward to meeting their new baby.

Since Melissa was 33 when Jack was conceived, she was “right on that cusp” for experiencing a higher-risk pregnancy for herself, or possible development issues with the fetus. Therefore, Melissa’s gynecologist recommended noninvasive prenatal testing, also known as a NIPT test. The results came back indicating there was a “70% chance that Jack had an additional chromosome.”

On the morning she received the results, Melissa had a moment of what she referred to as “mother’s intuition.” Despite being told it would be one or two weeks before the results of the bloodwork came back, she woke up, and decided to call out of work. Her husband did the same, they sent their daughter to school, and then called the doctor’s office to see if the results had come in.

The nurse on the phone told Melissa the results were in, and stated, “…everything looks normal, everything looks good,” before she trailed off. Melissa asked if the baby was a boy or a girl, to which the nurse replied, “Oh, I don’t know,” and asked if she could call Melissa back.

An hour later, Melissa’s doctor called. Melissa immediately knew something was wrong. As she recalled the doctor’s phone call, Melissa became very emotional. The doctor informed her there was something “not right,” and they planned to have the couple seen by a maternal fetal specialist that day. Melissa was told the “baby [had] an extra chromosome,” and she asked what that meant. The doctor said, “Well, right now it’s showing a 70% chance of this condition called Klinefelter Syndrome.” Melissa conveyed the news to her husband, and then put the phone on speaker so they could both hear the conversation.

At the end of the call, Melissa realized her question about the baby’s sex still hadn’t been answered, and she asked again if it was a boy or girl. The doctor said “It’s a boy, but don’t get your hopes up yet.” Melissa didn’t understand what the doctor meant, and wondered if that meant her baby was going to die. The provider had never had a patient pregnant with an XXY boy before, and therefore wasn’t able to provide much further information to the family.

Three hours later, Melissa and her husband were at the maternal fetal medicine doctor’s office to meet with a genetics counselor. A conversation with the counselor clarified some of the confusion from the conversation with the gynecologist. The counselor told them occasionally the NIPT test can give an XXY result after picking up the mother’s X chromosome, making it appear as though the baby has a second X chromosome. They were also told “Or, it may be a girl, and there’s something wrong genetically there.” The counselor indicated that while children with Klinefelter Syndrome aren’t as significantly impacted as those with more severe chromosomal abnormalities, there weren’t any guarantees about the type of life their child would lead. She said depending on where their child fell on the spectrum “he may never be able to live independently.” The counselor encouraged the family to focus on the idea that the test may be a false positive.

Melissa and her husband left the appointment with a renewed hope that perhaps the counselor was right, and the NIPT test had given a false positive. In order to confirm the diagnosis, Melissa and her husband opted for an amniocentesis. While lying on the table while the doctor prepared for the procedure, Melissa said, “So a lot of these (NIPT) are wrong, right?” The doctor said he’d “never had an NIPT test say XXY and the amnio comes out differently.” This news, which was so radically different from what the genetics counselor had told them, sent Melissa into an immediate panic attack. She said from “that day forward, it was very dark.” A week later, the results from the amnio came back, indicating the baby did have Klinefelter Syndrome.

Even though she knew in her heart what the results would be, Melissa felt “pretty hysterical” when given the news. The day they called, which happened to be a few days before Thanksgiving, Melissa was home by herself. She called her husband at work, so he “wasn’t able to respond much.” Melissa said she “shut down after that.” They told their immediate family, keeping the information limited to their parents and siblings.

Even though she knew in her heart what the results would be, Melissa felt “pretty hysterical” when given the news. The day they called, which happened to be a few days before Thanksgiving, Melissa was home by herself. She called her husband at work, so he “wasn’t able to respond much.” Melissa said she “shut down after that.” They told their immediate family, keeping the information limited to their parents and siblings.

Melissa felt as though they received a “mixed reaction,” after sharing the news of the baby’s diagnosis. A lot of people offered their condolences, and she said “you wonder to yourself what they’re sorry about, but you get it at the same time. Now that my son is here, and he’s just so perfect to me, I’m not sorry.” However, Melissa feels having gone through the experience of having a child with genetic differences, she’d be able to have a more empathetic response to someone sharing similar news with her.

After receiving the diagnosis, Melissa and her husband took to the internet to find more information. Her sister discovered Living With XXY, and the founder Ryan Bregante, which helped Melissa begin feeling more prepared. However, Melissa didn’t feel fully comfortable until Jack’s birth. Once he arrived, and she saw him, she knew everything was going to be ok.

Birth:

After gaining more understanding of the diagnosis, Melissa and her husband were able to turn their attention towards the other health issues their unborn child was experiencing. Melissa remained under the supervision of maternal fetal care until Jack’s birth, and was given extra ultrasounds to monitor his progress.

Jack was diagnosed with Intrauterine Growth Restriction, or IGUR. Since Jack wasn’t getting enough nutrients from the placenta, his growth wasn’t happening as rapidly as the doctors would have liked. They wanted to induce Melissa at 37 weeks, but since the baby’s stats were staying around the 10th percentile, they allowed her to decline the induction. Melissa was induced at 41 weeks, and Jack was born six hours later, weighing exactly six pounds, one ounce.

After a stressful, isolating pregnancy, and painful birth, Melissa found it difficult to immediately connect with Jack. Of the experience, she said, “it’s very hard. You’re severely depressed for seven months, go through a brutal, one hundred percent natural labor where you feel everything, and then this baby comes out, and they expect you to be like “give me the baby”! It’s a lot mentally. I think my mental health really played a part in how my brain reacted when Jack was born.” It took a few days for them to connect, an experience many mothers share following a difficult pregnancy and delivery. Melissa’s husband connected quickly with Jack, and within a few days, Melissa did as well.

Jack was born anemic, which led to some difficulties with the hospital when it came time for his circumcision. The pediatrician assigned to his case refused to perform the operation at the hospital, citing Klinefelter Syndrome as the reason for the refusal. The family left the hospital and took Jack to a pediatric urologist who was “very appalled” by the treatment they had received. The procedure had to wait until Jack’s anemia had been treated, so they were unable to circumcise him until he was six months old. Jack was given a karyotype test at birth, which confirmed the diagnosis of 47XXY.

Growth and development:

After his birth, Jack was in and out of hospitals for several months to manage his anemia. He also had torticollis, which is identified as the tightening of muscles in one side of an infant’s neck. As a result, Melissa began to push for early intervention services immediately. In New York, the Klinefelter Syndrome isn’t an immediate qualifier for early intervention programs, but Melissa refused to be told no. She pushed forward, fighting relentlessly until she was able to convince the program heads Jack did indeed qualify for services. He was enrolled in physical therapy at three months to address the torticollis , as well as other delays in movement. His physical therapist recommended occupational therapy to help address delays in his fine motor skills, particularly with his ability to use his fingers.

, as well as other delays in movement. His physical therapist recommended occupational therapy to help address delays in his fine motor skills, particularly with his ability to use his fingers.

In the hospital, Jack experienced issues with latching onto the bottle, which resulted in some weight loss. However, after some feeding therapy using a pacifier to help train the jaw and tongue muscles, he became a “great feeder,” and picked up weight at about three months. He now weighs 24-25 lbs, falling in the 70th percentile. Today, Jack eats well, but does experience some issues with texture. He refuses to eat steak or hamburger, which Melissa thinks could be in part due to his low muscle tone, as those foods are typically more difficult to chew.

Jack is what Melissa described as a “low muscle tone baby, specifically in his core.” She added “he also doesn’t have a lot of use of his left side, and they’re still working on it.” In particular, Jack “doesn’t like to transfer from one hand to another or use his left hand.” Overall, they’ve seen Jack’s muscle tone increase, he can jump, and he walked at 11 months and 3 weeks. Melissa reported all the therapies have “helped him tremendously,” and she doesn’t know if he would be where he is without them.

Jack continues to participate in early intervention programs. He’s currently seeing a physical therapist and occupational therapist twice a week. He was evaluated for speech therapy, after his occupational therapist suggested he may be experiencing low muscle tone in his jaw and tone, which can inhibit language development. After his third birthday, Jack will undergo further testing, and will qualify through the family’s school district for ongoing services.

In addition to 47XXY, at 15 months Jack was diagnosed with microcephaly, which is a condition where a child’s head doesn’t grow in proportion to their body. The family was shuttled around to every major hospital in their area. Melissa feels that because Jack had a previous diagnosis of Klinefelter Syndrome, this made the doctors extra precautions when it came to his secondary diagnosis. Jack has had an MRI, and a CAT scan, with Melissa commenting, “he’s been through every tube you can imagine.” She wondered if the same approach would’ve happened with her daughter, who doesn’t have any health conditions.

Melissa and her husband enrolled Jack in the Extraordinary Babies study, located in Delaware. They took Jack to participate in a series of developmental tests and evaluations with a speech therapist, occupational therapist, and endocrinologist at three, six, and nine months. While they were unable to attend his yearly appointment due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they plan to resume their visits for his second birthday. Following that, Jack will participate in the study until he’s nine years old.

At this time Melissa and Ryan don’t feel it’s necessary to have Jack start early testosterone replacement therapy.

Living With XXY:

Following Jack’s birth, the family didn’t initially make an announcement about his diagnosis. However, after his frequent visits to the hospital to treat his anemia, people in their lives became concerned about his health. After trying to figure out how to share the news with friends and family, Melissa and her husband decided to do so at Jack’s christening. Melissa felt it was the best way to educate everyone, so she and her husband made a speech, sharing Jack’s diagnosis. They told everyone Jack had Klinefelter Syndrome, what it was, and what they’d need to watch out for over the next few years of his life. They explained that parents of Klinefelter Syndrome boys, “get them services, and maybe one day he’ll need special education in school.” They told everyone they were prepared, knew what they were going to do, with all the right services and people around them. Even though the evaluations are hard to read, Melissa knows that understanding where Jack is at developmentally is important for helping him keep the services he needs. After the speech, Melissa remembered that the room “was very quiet,” and “There was a lot of crying.” However, despite the big emotions in the room, there was also a lot of support from everyone. To this day, many people still regularly check in on Jack to see how he’s doing, and if there’s anything the family needs.

When asked to describe Jack, Melissa said he’s a great baby. He has a calm, quiet personality, and has always been a great sleeper. He has a few words, including “hello, no, thank you, and baby.” Melissa said “he’s…the sweetest little boy,” who loves to give hugs and kisses. He attends daycare two days a week, providing the opportunity to socialize with other children his age. While Melissa didn’t necessarily say Jack had been diagnosed with Klinefelter Syndrome, she alerted the daycare providers that Jack had “some delays”. She asked them to keep an eye on him, and watch out for anything.

When asked to describe Jack, Melissa said he’s a great baby. He has a calm, quiet personality, and has always been a great sleeper. He has a few words, including “hello, no, thank you, and baby.” Melissa said “he’s…the sweetest little boy,” who loves to give hugs and kisses. He attends daycare two days a week, providing the opportunity to socialize with other children his age. While Melissa didn’t necessarily say Jack had been diagnosed with Klinefelter Syndrome, she alerted the daycare providers that Jack had “some delays”. She asked them to keep an eye on him, and watch out for anything.

However, whenever she notices something and brings it up with the daycare providers, they feel he’s doing fine, and feel he’s developmentally on track. The daycare provider was “really great” and said, “Listen to me Melissa, I know you’ve shared with us that Jack has some stuff going on, and I really don’t see a difference between him and any other 2 year old. He’s just a normal, happy boy.”

When continuing the conversation about Klinefelter Syndrome, Melissa generally refers to it as a chromosome abnormality. She doesn’t usually say it’s Klinefelter Syndrome, because “the minute someone Googles Klinefelter Syndrome, [she doesn’t] want them to see what’s on that screen.” However, despite the inaccuracy of the information available online, Melissa doesn’t want to hide who Jack is from himself or the world. Melissa fears Jack growing up and asking “why did you hide it all these years? Are you ashamed of it, or embarrassed of me?” She pointed out other children with chromosomal variances aren’t hidden away, but instead are celebrated, saying “It’s just who they are. I feel the same about Klinefelter Syndrome. Jack will one day know; we’ll somehow tell him. I’m not sure how that will go; I just want it to be part of who he is. I don’t want it to be this shock one day.”

While at age five, her daughter is too young to comprehend the nuances of Jack’s condition, she understands Jack is different. She understands he goes to multiple therapy sessions per week, which is something she never did.

Melissa and her husband are in the process of discussing the future of their family. While they had a spontaneous pregnancy with Jack, they’ve been contemplating having another boy. They thought perhaps another son could donate sperm to Jack, or perhaps a sister could donate eggs. However, Melissa also finds these thoughts overwhelming, and says it’s hard to think about what Jack’s fertility plans will look like in the future. Additionally, the family was told by the genetics counselor that their chances of having another child with a chromosomal abnormality was 50% after having Jack, which feels like a “big risk” to take when planning another pregnancy.

Melissa and her husband are in the process of discussing the future of their family. While they had a spontaneous pregnancy with Jack, they’ve been contemplating having another boy. They thought perhaps another son could donate sperm to Jack, or perhaps a sister could donate eggs. However, Melissa also finds these thoughts overwhelming, and says it’s hard to think about what Jack’s fertility plans will look like in the future. Additionally, the family was told by the genetics counselor that their chances of having another child with a chromosomal abnormality was 50% after having Jack, which feels like a “big risk” to take when planning another pregnancy.

When asked what she would say to another mother receiving a prenatal diagnosis of Klinefelter Syndrome for their son, Melissa stressed the importance of having someone to lean on. When she found out about Jack’s diagnosis, she joined a toddler mom group on Facebook. She met a woman who was one week behind in her pregnancy, who was from Manhattan. Melissa and the woman talked weekly, and Melissa reflected “she was the one that got [her] through that pregnancy.” The two were able to share information, discuss how appointments went, and connected closely throughout their pregnancies. She thinks it’s important to speak to another mom who’s gone through it, someone who understands the difficulties, fear, and worry that can come with the diagnosis. She said it’s hard to have hope until the baby is actually here, and in the meantime it’s really helpful to have that support system.

Melissa also encourages parents of XXY boys to “Fight. Fight really hard. When he’s here, get every service you can think of…upfront in the beginning. Have him see a urologist, have him see an endocrinologist, and kind of put your mind at ease. I think the most important thing is to fight.”

Hello,

Do the anemia and microcephaly have anything to do with the KS diagnosis? I have not read about that before and am curious. Wishing your family the best. Thank you.

Hey Katie! Generally, those are not symptoms specific to Ks. Some boys and men with Ks have secondary or tertiary diagnoses as well.