Our Genetics Counselor Said Most People Terminate Their XXY Pregnancy

By Chelsea Castonguay

Karla is a 61-year-old guidance counselor from North Oakland County, Michigan. She’s the mother of Logan, who’s 31-years-old. Logan lives with Klinefelter Syndrome (47 XXY) and was diagnosed prenatally.

Diagnosis:

Karla was 34-years-old while pregnant with Logan. Her pregnancy initially began like her two previous pregnancies, but at around two months gestation she began experiencing bleeding. Her doctor told her it could be a spontaneous miscarriage, so Karla rested for a few days. The bleeding stopped, and everything appeared to be fine.

Due to her age, and the history of bleeding, Karla’s doctor suggested a blood test to make sure everything was ok. When the results of the test came back, Karla was informed something “was amiss” with the baby. It was initially thought perhaps the baby had something like Down Syndrome, but the doctor wasn’t sure what was going on. Karla had an amniocentesis, which confirmed her son Logan had 47XXY.

The doctor called to deliver the test results over the phone, but didn’t offer much more in the way of support or information. After she received the news, Karla was distraught, and called her sister-in-law in tears. When her husband came home from work, Karla informed him of the diagnosis. Her doctor wouldn’t discuss anything more over the phone, instead telling Karla she’d be referred to a geneticist. Karla was in shock, and felt as though the information should’ve been shared in person, not over the phone.

Karla called Wayne State University to get an appointment with the geneticist, but it took several days before they could be seen. In the meantime, Karla continued trying to absorb the diagnosis. Not knowing anything about Klinefelter Syndrome, she imagined her child might be wheelchair-bound, unable to speak, or unable to live an independent life. She worried about her ability to mother a child with such significant needs, but knew termination wasn’t an option for her.

The genetics counselor didn’t have much further information to provide, telling Karla and her husband most people who received the diagnosis of Klinefelter Syndrome choose to terminate the pregnancy. Since she was already several weeks into the pregnancy, she’d have to decide within a week. The counselor told Karla that Logan would most likely be “very tall,” and that most people with Klinefelter Syndrome have a lot of “issues from mild to severe.”

The minimal information provided didn’t soothe Karla’s fears. She was a nervous wreck, and was unable to sleep or eat. Desperate to learn more, she went to the  local library to continue researching. However, what she found was “devastating.” She stumbled upon a book that discussed Klinefelter Syndrome, but used prison inmates as a control group. The implication was that individuals with Klinefelter Syndrome would be “deviants” who ended up incarcerated, or worse. Her research led to a conversation with a doctor based out of Colorado. The doctor spent an hour on the phone with Karla, answering her questions and reassuring her by saying Klinefelter Syndrome is not a “death sentence.” In fact, he told Karla that while there’s a range of how individuals are impacted, many go onto college, and live productive lives. He encouraged her to ignore the negative information she encountered, especially the book with the men in prison.

local library to continue researching. However, what she found was “devastating.” She stumbled upon a book that discussed Klinefelter Syndrome, but used prison inmates as a control group. The implication was that individuals with Klinefelter Syndrome would be “deviants” who ended up incarcerated, or worse. Her research led to a conversation with a doctor based out of Colorado. The doctor spent an hour on the phone with Karla, answering her questions and reassuring her by saying Klinefelter Syndrome is not a “death sentence.” In fact, he told Karla that while there’s a range of how individuals are impacted, many go onto college, and live productive lives. He encouraged her to ignore the negative information she encountered, especially the book with the men in prison.

Karla decided to go through with the pregnancy, and Logan was born healthy. Following his birth, Logan experienced some health complications that kept him in and out of the hospital until his toddler years. She found Logan wasn’t able to fight off childhood viruses like her other sons did.

Raising Logan:

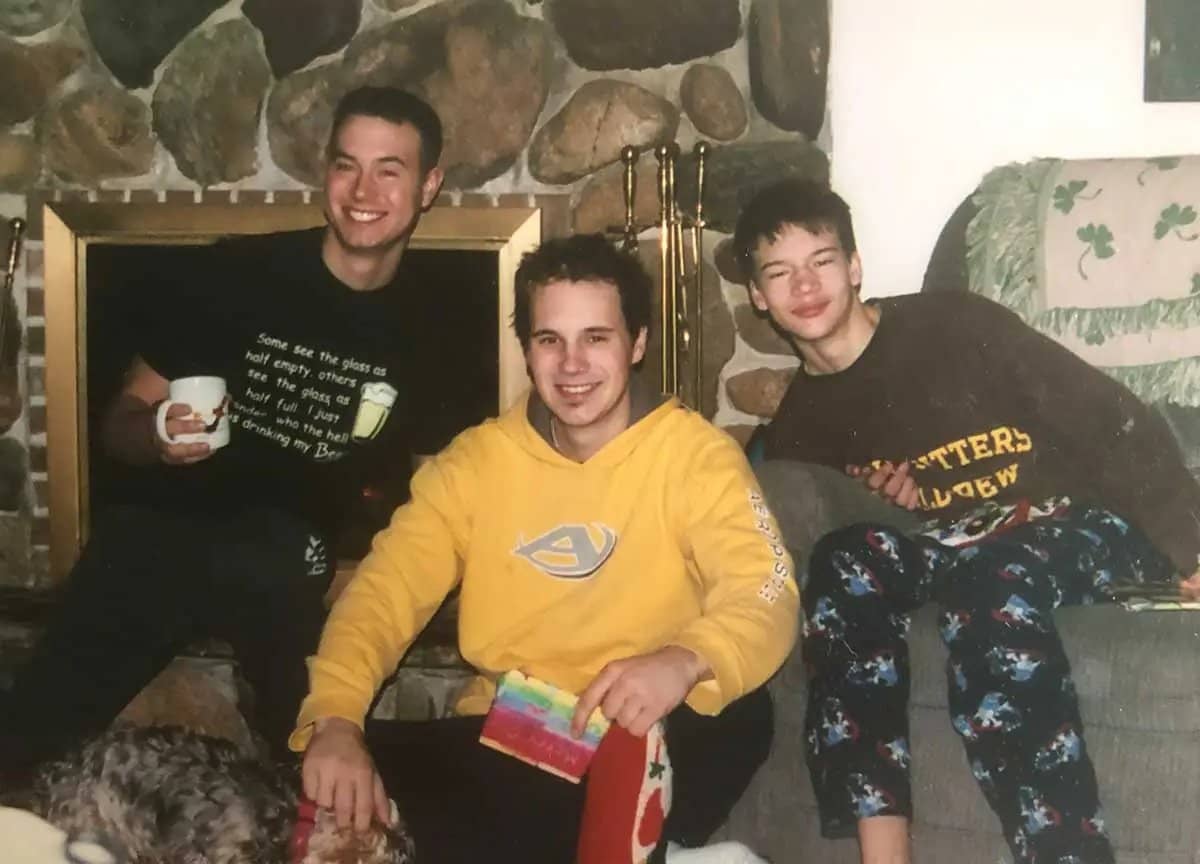

In the beginning, Karla and her husband told only a few people about Logan’s diagnosis, bringing her parents and sister-in-law into the fold. The people they told responded to the news “ok,” but the family continued to keep it to themselves for the most part. An elderly aunt stepped in to help Karla, and said “all the right things” to comfort her fears and worries about the baby. As her older sons were only five and seven during her pregnancy, she didn’t share the diagnosis with them at that time.

As Logan grew, Karla continued her research, and realized if they wanted Logan to live a “normal” life, the family would need support. As Logan was experiencing developmental delays, he was given an interview at an early-intervention preschool. His speech was delayed, and he needed help to develop his fine motor skills. Teachers came to their home to work with Logan on strengthening his core muscles, and helped with speech. While Logan was shy as a child, he eventually began opening up, and became more outgoing. As Logan grew, Karla and her husband explained to their two older sons that Logan was a bit different, and took things slower. However, they “didn’t treat him with kid gloves or anything.”

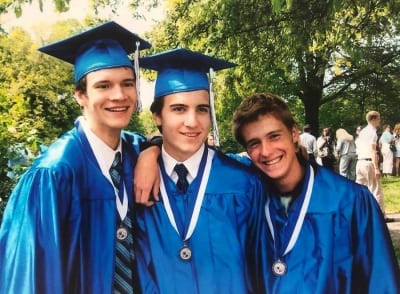

. Since Logan’s teachers needed to know, Karla decided to no longer keep the diagnosis a secret and tell other people. Everyone accepted the news without issue. Logan had an IEP until 4th or 5th grade, but never needed specialized classes. He was able to keep up in school, and earned average grades.

. Since Logan’s teachers needed to know, Karla decided to no longer keep the diagnosis a secret and tell other people. Everyone accepted the news without issue. Logan had an IEP until 4th or 5th grade, but never needed specialized classes. He was able to keep up in school, and earned average grades.

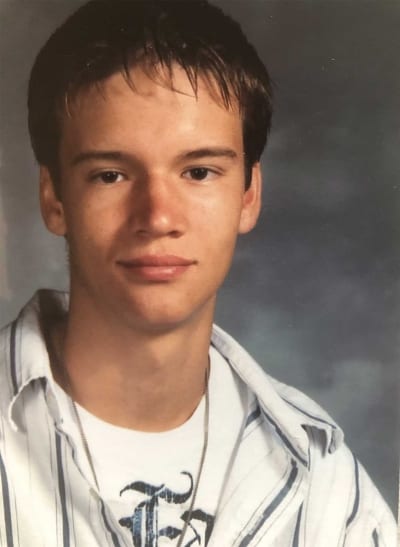

Around the time Logan was six or seven years old, Karla and her husband told him about the diagnosis. They were very open with Logan, explaining that it was something he may have to deal with as he grew older. Logan took the news in stride, understanding that Klinefelter Syndrome “was just a part of him.”

When Logan entered puberty around age 11, the family connected with an endocrinologist who had other Klinefelter Syndrome patients. The doctor explained everything about Klinefelter Syndrome to Logan, and quipped, “Now, because you are infertile it doesn’t mean you can go around sleeping with girls, because you know you can still get diseases!” Logan began receiving testosterone replacement therapy at this time, with shots injected in his upper thigh. Karla administered the shots for about six months, and then Logan took over from there.

The endocrinologist regularly monitored Logan’s testosterone levels, and told them when it was time to do another treatment. They also scanned Logan’s joints, and discovered they weren’t fusing at that time, but testosterone seemed to help slow his growth. He’s been on injections since, and hasn’t utilized any other methods of testosterone replacement. At around age 14, they tested Logan’s sperm to see if any were viable, but found he had no viable sperm. This didn’t bother Karla, and wasn’t an issue at all, nor was it an issue for her husband. Logan wasn’t bothered by the news, either.

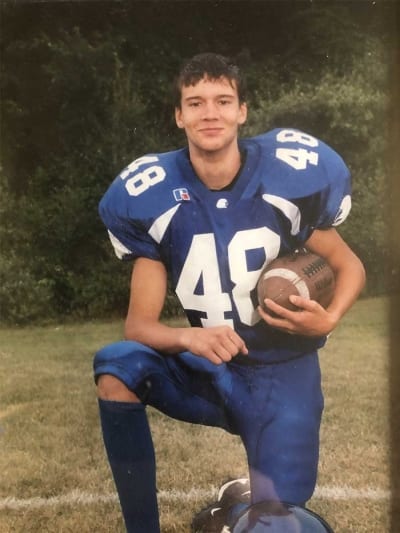

Once Logan entered his teens, the impact of the testosterone treatments became more obvious. He grew to be six feet, four inches, and experienced physical

delays in puberty. While her other sons were stockier, Logan was tall and thin. As the testosterone left his system, Logan experienced mood swings, alternating from tears, to flares of anger. He experienced bursts of anger that left him feeling out of control. He could tell when his levels were dropping, and would yell, “I haven’t had my T shot and I know I need it!”

To help him with the emotional problems he was experiencing during his teens, his parents took him to counseling. Karla related that perhaps the counselorwasn’t the best fit for him, but after their time together he developed better coping skills to handle his mood swings. However, Logan was also empathic, and loving. He was much cuddlier than her other sons. As a child, Logan was content playing on his own. He had two or three close friends throughout high school, and participated in track.

Living With XXY:

As an adult, Logan lives on his own with roommates, maintains full-time employment in construction, and is learning woodworking. He also has been involved in a long-term relationship, and checks in with his family every few weeks.

member for men with 47XXY, and Karla belongs to a similar group for mothers of boys with 47XXY. Joining the group has been a positive experience, as it’s allowed her to read stories about other families’ experiences. She’s grateful they were able to get an early diagnosis for Logan, so they could monitor his development while he grew up.

member for men with 47XXY, and Karla belongs to a similar group for mothers of boys with 47XXY. Joining the group has been a positive experience, as it’s allowed her to read stories about other families’ experiences. She’s grateful they were able to get an early diagnosis for Logan, so they could monitor his development while he grew up.

When asked what she would share with another mother who just got a Klinefelter Syndrome diagnosis, Karla said “it isn’t the end of the world. Have a lot of faith that the kids are very loving, and they will be your wonder child.” She added that a lot of kids have other issues, and the Klinefelter Syndrome diagnosis isn’t bad. It can be a little struggle, but nothing devastating.