Klinefelter Syndrome: Building A Community With Ryan Bregante.

Klinefelter Syndrome. When Ryan Bregante sees statistics estimating that 1 in 500 males has the extra X chromosome that causes Klinefelter syndrome. He is acutely aware of his minority status as the “1” in that equation. Another statistic is ever-present to him as well: as far as researchers have been able to determine. Only some 3 in 10 males with Klinefelter even know they have the condition.

That makes Bregante a minority of a minority. Unlike the 70 percent of males who must deal with the challenges posed by Klinefelter syndrome without any context for understanding their source, Bregante has known about his extra X since he was 9 years old. Ryans’ parents, in consultation with the family pediatrician, decided its perfect timing to let him know.

The result of that conversation? It would seem to fit the classic dictum, “Knowledge is power.”

At age 32, Ryan Bregante is full of knowledge not only about Klinefelter syndrome. But also about the wider world, he has embraced and held close ever since he can remember.

Now armed with that knowledge and the tireless support of parents who have encouraged him from his earliest days, he is cutting an indisputably powerful path through a Klinefelter syndrome world he hopes to move toward greater openness, greater acceptance, much greater networking, and a wider, more positive lens through which the condition should be viewed.

He is, in short, on a mission to change almost everything about the way males with Klinefelter Syndrome experience the condition, and the way those around them understand it.

“When I posted my first question on a Klinefelter syndrome Community Facebook page, ‘What are the positive attributes you enjoy about your condition?’, oh my God, I got 300 replies.”

Gateway to the east…

Social Media Tour

Bregante recently returned from an extended seven-state east coast swing that began just after the new year. He flew from his home in San Diego to Washington, D.C. He was to appear before a Food and Drug Administration panel investigating new medications to treat low testosterone, which is one of the chief characteristics of Klinefelter syndrome.

“The hearing was for a pill that could be another option besides gels or injections for testosterone replacement,” he says. “Low testosterone affects millions of men, and Klinefelter syndrome is only a small part of that group. The company that produced the drug felt the FDA testimony would be helpful to its approval, and it’s important that the FDA hear from us about what the concerns are.”

FDA testimony behind him, Bregante then rented a car to road-trip for nine days and 1,700 miles through Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee before heading up to Pennsylvania and then home. The entire trip focused on meeting up with and connecting people affected by Klinefelter syndrome, whether directly or in support of family members.

“I made a spreadsheet with 600 people, picked up I don’t know how many new Facebook friends, and tried my best to put kids together in the same town who have Klinefelter syndrome and may have lived just blocks or minutes from each other and had never met.

They thought they were alone, what (Klinefelter syndrome researcher) Sharron Close at Emory University calls, ‘hidden in plain sight.’ It was great to see them come together. If you’ve felt alone for years because you’ve never experienced a Klinefelter syndrome community, it can be life-changing.”

With the gentle urging of Bregante’s parents, he attended the AXYS conference for Klinefelter Syndrome.

“When my parents first mentioned it, my response was, ‘Meh…’” he says. “But I try to keep an open mind on things so I finally said O.K. I went and met amazing people the whole time. When I researched what AXYS did and didn’t do well, I saw there was a need for social media as a way to build a greater community. That’s when I decided to start a YouTube channel.”

The Power of Video

A selfie at Arches National Park, Utah

Ah, yes, YouTube. Most people are so used to Hollywood actors coming across as “real” and unself-conscious on camera. They have no idea how hard it is. They don’t see how much fear-and-trembling can be involved—until they stare at the red recording light themselves.

That’s when they experience how flustered and frozen it can leave them as they “Ummmm…” their way into a big, embarrassing plop of jelly.

So here we see Bregante, confident, upbeat, and cool in an engaging series of YouTube videos. Better still: despite executive function challenges that tend to come with Klinefelter syndrome, Bregante plans, produces, directs, and stars in all the videos by himself.

In them, Bregante looks directly into the camera and talks about life with Klinefelter Syndrome. No notes or the help of a director, nor any editing of the tape itself.

What we see is what we get, and what we get is a handsome, dark-haired, highly verbal, and naturalistic young man, seemingly at ease with the camera, himself, and the condition he is reflecting upon.

No theatrics or entertainment flourishes, no groping for words, no woe-is-us. Just the straight, reassuring scoop from a Klinefelter “sufferer,” as the popular medical parlance might have it, as he holds forth on how dimly he views the all-too-widespread understanding of Klinefelter syndrome being a kind of death sentence for an interesting and rewarding life.

“Can I marry you?” gushes one viewer in the first of the 10 videos Bregante produced since returning from the AXYS conference last summer. And in a far more sober vein, another commenter writes this:

“This has been so helpful. We just found out my son may have it through an early noninvasive chromosome test and I was so upset because I have seen horror photos and stories and this is the first voice of reason I’ve come across…I am gonna have a second test to be sure but if it’s not a false positive I’m gonna start him with the treatments early so he can be okay…I was so scared and even considered an abortion…you look so happy and healthy so this helps me a lot thank you.”

That kind of testimonial, which Bregante says continues to come in from around the world from parents, grandparents and those with the condition themselves, most always express some form of thanks that someone, finally (FINALLY!), has helped “normalize” a genetic variation that still leaves their bearers far more like every other human being in the world rather than some kind of freak fit for a museum.

“When I posted my first question on a Klinefelter syndrome community Facebook page, ‘What are the positive attributes you enjoy about your condition?’, oh my God, I got 300 replies,” Bregante marvels. “That’s when I told myself: ‘I need to do more of this.’”

“We walked out of the geneticist’s office thinking, ‘Well, we’re not perfect, why should we expect our son to be?’”

Indulging the KS gift of “acute sensitivity”

Parental Guidance

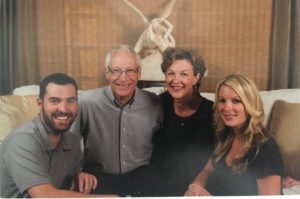

Bregante’s can-do approach has no doubt sprung and flourished from the rich legacy of his parents, Richard and Rosalie, whom Ryan continually refers to (along with his paternal grandfather) as the primary sources of his inspiration and personal resolve.

As older parents with well-established legal careers before Ryan was born (Rosalie was 42, Richard 49), the couple has always taken a practical, studied, and patient approach to dealing with their son’s condition.

When a genetic test revealed Ryan’s extra X chromosome and this condition they had barely heard of before, they were concerned but not overcome, looking to the meager public resources and information there was at the time to inform their approach to what lay ahead of them.

Much library time followed in those pre-Internet days. Along with a big assist from a geneticist who explained some of the challenges their son would face.

The geneticist also emphasized studies citing the importance of early and consistent intervention, and how vital language training is in mitigating later speech and cognition challenges facing those with Klinefelter syndrome.

“We walked out of the geneticist’s office thinking, ‘Well, we’re not perfect, why should we expect our son to be?’’ Rosalie remembers. It is a theme Richard returns to later in the conversation when describing Ryan’s school years.

“We took the approach, ‘What’s perfect in this world?’ he says. “Ryan had classmates who were diabetic and had other conditions, too. Ryan has Klinefelter syndrome. It’s a part of who he is, but it is not the sum total. Everyone has something, some challenges in life. We did not want him to be a victim.”

Adds Rosalie: “We emphasized that there is almost always a way around a problem, a different way of accomplishing something. An easy example is a fact he can’t father biological children. But there is no barrier to him adopting. He’s always been deeply sensitive and caring, and he took to that idea very quickly.” (Note: Ryan has dated since high school but he remains single and without children by choice.)

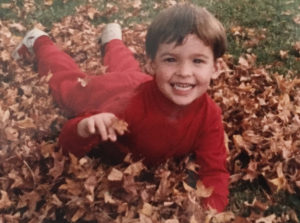

Little League portrait

Standing Up for Himself

His parents both recall an incident when Ryan was in elementary school and had a classmate who had been bullying him

“He hadn’t said much about it, only that he’d been having a problem with one kid,” says Richard. “One day, the kid made some crack, and suddenly they were on the floor. Ryan just took him down, right there in the classroom.

He got in some trouble for it. But I don’t think the principal was displeased that Ryan had brought it to ahead. Personally, I thought he had a lot of guts to do something like that. I was secretly pleased.”

The incident suggests some of the movie and outward confidence Ryan has carried with him into adulthood. Though he admits it is sometimes elusive. “One of the things that come with Klinefelter syndrome is a tendency toward anxiety. Everyone tells me how well-spoken I am, but when I’m feeling anxious, that kind of thing comes in one ear and goes out the other.”

One can’t help noting, however, the confidence revealed in him being able to observe and admit to such insecurity, insecure people often working as hard as they do to keep a façade of outward swagger.

“And then there was Ryan himself, who struggled socially and being teased in the often unforgiving milieu of elementary and middle school.”

A Family Journey

The family at home, 2016

His parents also don’t wish to sugarcoat the challenges the whole family faced in dealing with Klinefelter syndrome. In a profound sense, one member’s diagnosis becomes the entire family’s. With each member having to adjust to its peculiar demands.

Richard and Rosalie remained attentive as possible to Ryan’s sister Richelle (older by three-and-a-half years and with the standard 46-chromosome XX makeup), lest she suffers the fate of many “normal” siblings who feel their concerns and lives are washed over by the extraordinary attention and resources lavished upon their sibling with special needs.

“I suspect it wasn’t easy for her, but we never had to worry about her,” Rosalie says. “It was another way in which we were lucky.”

For her own part, Rosalie was five months pregnant with Ryan when an amniocentesis revealed his condition. Still working as a medical malpractice attorney while tending to his pre-school age sister at the time, she made the decision to forsake her career and become a stay-at-home mom.

“I never regretted it, though before I quit, I remember being at home and wishing I was at work, then when I was at work, wishing I was home,” she says. “What I learned, though, is that being a full-time mother is harder than any career one can pursue outside the home.”

And then there was Ryan himself, who struggled socially and being teased in the often unforgiving milieu of elementary and middle school. The more rigorous academic of high school further intensified the challenges he faced.

“Getting him through high school was like pulling teeth,’ Richard muses, to which Rosalie adds: “The day he graduated was one of the happiest days of my life.”

Richard again: “I also believe in the power of prayer, and there was a lot of that going on then!”

School Struggles

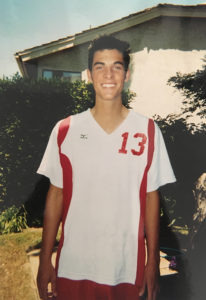

The high school volleyball years

Like many boys with Klinefelter syndrome. Ryan, gifted visually, taking naturally to puzzles, Legos, anything else requiring visual memory and kinetic skill. He lapped up everything he could about computers at one summer camp.

“He can do anything with his hands,” Rosalie says. “His right brain, artistic talents, and hard work ethic have compensated for the learning disabilities that come with Klinefelter syndrome.”

Auditory processing is another matter, though, making it a serious challenge for boys and even adult males with Klinefelter syndrome to follow the standard lecture-and-note taking regimen prevalent in traditional education.

Those processing difficulties cause many such students to just give up and grow disinterested in furthering their education. Bregante readily acknowledges the struggles in his high school years. Having to quit his much-beloved volleyball team in his junior year.

He was a starter on a fine San Diego area team where volleyball is a very big deal. Unfortunately, his grades had slipped beneath the eligibility criteria.

“We had a great team, but I had to go to my coach and teammates and tell them I was ineligible,” he says. “I let everybody down—my coach, my team, my family, myself. It was one of the most awful but best things ever to happen to me. I realized the consequences of not working hard enough, not taking care of things, and then failing.”

To which he adds, with an undercurrent of deadpan humor: “Then my girlfriend broke up with me, besides.”

“Acute taste sensitivity is one of the gifts of Klinefelter syndrome. And that led to Bregante’s natural interest in putting ingredients together and making something tasty and memorable for others.”

Career Search

Getting an early start on his chef career

However much Bregante recommitted himself to academics (he worked his way back onto the volleyball team his senior year). Success in that realm rarely comes without a great struggle for those with Klinefelter syndrome. He remains well aware of the challenges.

“People with Klinefelter syndrome have executive function issues, so things, like getting to class on time and managing time for homework, can be really hard,” he says. “My parents also taught me that struggles are also a state of mind and that a lot of problems also come with just regular life and have nothing to do with Klinefelter syndrome.

“My dad’s father, my Grandpa, came over from Italy with nothing, and my mom grew up poor on a farm in Idaho, picking potatoes. She saved all through high school so she could go to college. If there’s anything

I’ve learned from all of them, it’s the value of hard work, that if you keep going, if you put in those 10,000 hours of practice on something that the books tell us about, you are going to get a whole lot better, no matter who you are or what you’re doing.”

Ryan accumulated a good portion of the 10,000-hours-goal made famous in Malcolm Gladwell’s book, The Outliers, when he pursued childhood passions not only in volleyball, but also basketball, baseball, and even the drums in forming a garage band that actually played at dances and such, though Richard drily observes about the latter, “They weren’t very good.”

And there was also food and cooking, at which he was and remains very good. Acute taste sensitivity is one of the gifts of Klinefelter syndrome. And that led to Bregante’s natural interest in putting ingredients together and making something tasty and memorable for others.

The upshot of all these factors was a decision to skip the grind that college promised. And went to culinary school instead. But rather than stay close to home and all its security. Bregante opted to attend the renowned Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York.

It was an education not only in gastronomy but also in forging an independent life. Three years later, he took off for Vail without knowing a soul there. He landed successive jobs in well-heeled restaurants while finding roommates on Craig’s List.

In his off-hours in that fabled mountain town, he taught himself both photography and snowboarding. Ultimately becoming so good and well-connected in both. He left the grind of being a restaurant chef for the more freewheeling world of photographing. Often photographing breathtaking antics of snowboarders and landscapes.

Then it was the hustle of selling his photos to magazines and whomever else was in search of them.

The career change also saw him move to Salt Lake City, the unofficial snowboarding capital of the USA. “Much cheaper than Vail,” Bregante explains. “Snowboarders are not so much into money.”

“It starts by creating community. Talking about it with others leads to understanding that you don’t have to feel shame.”

With his gang at a recent Klinefelter syndrome Community meetup, he organized through Facebook

Back Home…With a Mission

Still, life as a freelance photographer has its limits in this digital age of countless cheap stock photo sites. Bregante wound up moving back with his parents in 2015. Basically, he says, “because I was broke.” He has since moved in with friends in the San Diego area.

He supports himself mostly by staging private chef events. He is also stoking his passion to teach the world everything there is to know about Klinefelter syndrome.

The most important piece of that? “It starts by creating a community. Talking about it with others leads to understanding that you don’t have to feel shame. Everyone is on some spectrum or other.”

Talking about community takes him back to his foundational high school years again. “I started to get a really negative perspective on things when I was about 16. I thought at the time it was because both my parents were lawyers, but I realized it was just me. But my friends called me on it, and they did me a huge favor. It made me see how my negativity was affecting everything I did.”

Several years later, that negativity resurfaced as fear during his snowboard photography stint. I freaked myself out a lot when it came to backcountry photography. Avalanches happen to even the most experienced photographers and snowboarders. “It paralyzed me from taking photos in more risk/reward areas.”

“I worked hard on that, and it helped me to see later how much bitching, moaning, and naysaying can affect people with Klinefelter syndrome.” You see it all the time on the Internet, but it sure doesn’t help that when you Google ‘Klinefelter syndrome,’ the first thing you see is a Mayo Clinic illustration of a young man with large female breasts. The fact that you can control that symptom and many others doesn’t come through until you dig a lot deeper.

“That’s just one of the challenges we face, and it’s as much about educating the medical community in how they talk about Klinefelter syndrome as anything else. The negativity also causes people with Klinefelter syndrome who are successful and lead great lives never to talk about their condition. People hide from it, but by talking about it, they can change the world.”

He points to other conditions as models of what he is aspiring to for Klinefelter syndrome.

“Look at breast cancer, Down syndrome, autism: all of these conditions have huge communities behind them. They’re well-known. But Klinefelter syndrome remains invisible because the condition is buried in the genes we carry. No one looks at me on the street and says, ‘Oh, he has a genetic variation.’ So we need to tell people about it and talk to each other, too. We need to bring it out to the world.”

Yes, Ryan Bregante has a passion to burn on this subject. And good luck to anyone who would try to hush him now.

“There’s so much positivity in Klinefelter syndrome!” he exclaims. “I would never want to be any other way. We start just by being ourselves. And 30 percent of us who are lucky to have a diagnosis and get treatment to have a special responsibility. We have to do everything we can to raise awareness. So the other 70 percent can get the help and support they deserve.” You can help our community grow.

Writer and editor Andrew Hidas website project last year and manages AXYS organization’s Annual Fund mailers. Previously, he edited the journal of the National Fragile X Foundation for many years. He blogs at Andrew Hidas